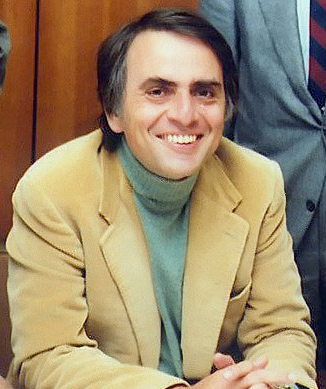

In The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan tells the story of the fire-breathing dragon living in his garage.

Spoiler alert: there’s no dragon. There is, however, an amusing anecdote that demonstrates some very weird things that can happen when you ignore evidence (or the lack thereof). As Sagan tells it, a friend comes by to see the dragon, and Sagan explains that it’s invisible. The friend asks him to spread some flour on the floor so they can at least see its footprints. Sagan says it’s a flying dragon. The friend suggests an infrared camera to detect its flames. Sagan explains that it breathes heatless fire, and so on, and so on, and so on.

In the end, Sagan asks the reader what the difference is between an invisible, flying, incorporeal dragon and no dragon at all. The answer is: none, unless you choose to ignore the complete lack of evidence for any dragon.

Another great example of what happens when you ignore evidence (and a good example of cognitive bias) is contained in When Prophecy Fails, a classic work of psychology from 1956. It examines the activities of a Chicago cult which believed an apocalyptic flood was about to hit the earth, and only by following a specific set of procedures could members be saved by a flying saucer that would whisk them to safety.

Spoiler alert: there was no flood and no saucer. But curiously, after the magical craft failed to appear, the most strident cult members didn’t reassess the new evidence (no flood, no saucer) and adjust their actions and beliefs. Instead, they ignored the evidence and doubled down on their emotional investment in the cult.

When people turn off their critical faculties and make evidence take a back seat to what they want to be true, dangerous things can happen:

- There was no wave of communists infiltrating America during the 1950s, but that didn’t stop Joseph McCarthy from destroying lives in an effort to smoke them out.

- Jews weren’t responsible for Germany’s post-WWI woes, but that didn’t stop Hitler from scapegoating them.

- There was no child sex trafficking ring run by Hillary Clinton and others, operating out of the basement of a Washington pizza parlour, yet QAnon is a viable conspiracy theory to this day.

When we adopt an evidence-first approach to information, we put a powerful shield on our arm that protects us from a ton of disinformation.

- Remember to ask, “What’s the evidence?” It doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about flying saucers or who makes the best spaghetti in town: our decisions need to be guided by evidence, and not what we want to be true.

- Look at the source of the evidence. Is it credible? Is it believable? How do you know? Nobody wants to critically examine every single piece of information they come across in life, but the more we look at the underlying evidence, the better decisions we make.

- Who’s got the best track record with evidence? Since we can’t evaluate every piece of information in life in detail, we need to take the shortcut of identifying trusted sources. Even then, we don’t turn off our critical faculties, but we recognize that these are the sources more likely to be worthy of our trust.